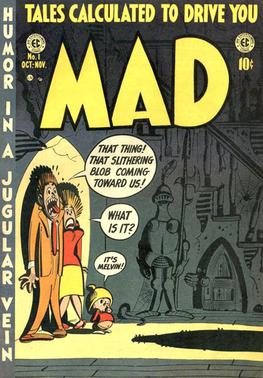

While we celebrated our nation’s 243rd year of independence last week, many also mourned the death of a nearly 70-year-old American institution—Mad magazine.

I, along with most, were jarred by the news. But if anybody is surprised, then they clearly aren’t paying attention to what’s happening in this industry.

As terrific as Mad was for generations, it failed in the same way many other magazines have over the past 15 to 20 years. It rested on its laurels, and continued to build its business around a print magazine with a frequency that was cut (too late) from monthly to bimonthly… for an audience that is now preoccupied by mobile devices.

I apologize if this sounds cold. I truly loved Mad when I was younger, and still believe it created some of the best American satire over the past several decades. And right up to the end, its covers made me chuckle and I continued to admire its irreverence and cutting social commentary. Still, its time has come, and mourning another magazine’s death would become very tiring in my role.

So instead I have to ask: how did we get here? And I don’t mean Mad magazine specifically, as it is merely another victim of a serious illness that will continue to infect print publications, which I believe is intensified by frequencies.

Weeklies were the canary in the coal mine more than a decade ago, as we saw the number of them slowly diminish, or move to biweekly or even monthly models. Kudos to those weeklies who are still making it work, but let’s face it, they are exceptions to the rule.

But let’s look at the past couple years, and what has happened to consumer print magazines with regular frequencies. Aside from the several titles I won’t name that completely axed print, others like Glamour and Seventeen have closed the door on regular frequencies and intend to publish occasional SIPs. Meanwhile, a slew of others including Rolling Stone, Popular Science, Entertainment Weekly (more than a bit ironic with its name) and Harvard Business Review, have scaled back their frequencies to make print more viable, and provide the flexibility to focus on other, potentially more lucrative (or at least more efficient) channels.

All too often when this happens, those who cover the industry, myself included, frame these pivots as failures, or as last ditch efforts to save their dying brands. That’s not always the case. Print isn’t failing because people want a lot of it, but aren’t getting it the right way. Print is failing because its expensive to produce, it doesn’t provide enough quality data for advertisers and the demand for it is shrinking. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a demand, which is why lowering frequencies is a strategy more magazines should consider.

The beauty of print is that it’s tangible. It’s portable. You don’t need to plug it in or charge it for a long trip. You can rip out a page and pass it along to somebody, or save it because it has a recipe you have to try. Plus, there’s an implicit feeling that what’s printed on paper is more permanent than what you see on a screen. However, we have become attached to our phones, and many of us stare at a computer all day. We have changed; and so has our need for print. It’s time we all embrace this idea.

That said, print is still a wonderful medium and there is still a place for it. But maybe we just need less of it? And by less I don’t just mean fewer issues, or fewer magazines, but I also mean less crap inside of a magazine. We should lean into all the unique qualities print has to offer readers, and only publish things that truly live up to its high standards.

So no, print isn’t dead, nor do I think it’s dying. However, it is sick, and frequencies are one of its most serious ailments. Some magazines will remain immune, while others will not. My only hope is those that are not act before they end up like Mad and the others who perished before it.

The post It’s Not Print That’s Broken, It’s Frequencies appeared first on Folio:.